Not too long ago, I was rushing from one informational meeting to the next, trying to gather the scoop on medicine, medical school, and what exactly it meant to be a pre-med (I found it strange that these three rungs on the medical ladder were not necessarily complementary with each other… Did acing a nit-picky orgo exam really hold any bearing on my future abilities as a physician?). During my data-gathering in college, I soon saw a common theme emerging from all of the advice I accumulated.

Regarding the medical school experience: Medical school is tough.

I was told that the material would be overwhelmingly vast, that I would spend most of my spare time with my nose in the books, memorizing, and that I should not even think about third year yet, because that was a whole ‘nother story. I was not deterred—I had found medicine (or rather, medicine had found me) and I could not imagine myself pursuing any other field. I was a little afraid because I knew I was not much of a memorizer. But, I would try my best. This all happened after my sophomore year of college, when I finally decided to “go pre-med.” (My path to choosing medicine will have to wait for a future blog post… stay tuned!).

I couldn’t imagine being busier than I already was. I was already heavily involved with three extracurricular activities, was starting to go into a lab to do research, and had a full course load. Yes, medical school was probably going to be busy—everyone said it would be—but somehow, I couldn’t wrap my mind around a life busier than what I was experiencing in undergrad. If I had been a more pro-active of a pre-med, I might have planned for the time-suck that I heard medical school was going to be. Maybe I would have started studying anatomy on my own, flipping through an atlas over the summer and starting to put down to memory muscles and nerves. Maybe I would have freshened up on my biochemistry or genetics.

Either way, I don’t think it would have prepared me at all for the balancing act that attending medical school has been. (In any case, I’m glad I didn’t fritter away my summer with a Grant’s Dissector.) It’s true that I’ve never been expected to memorize so much material in such a short period of time ever before. And that my attending lecture, small groups, and mandatory clinic sessions have resulted in much more class time (and hence, less free time) than in undergrad. Yet, these challenges are singular, and I have come to accept them as essential parts of the path I have chosen to take. The real challenge arches over other aspects of my life. It is the challenge of prioritization.

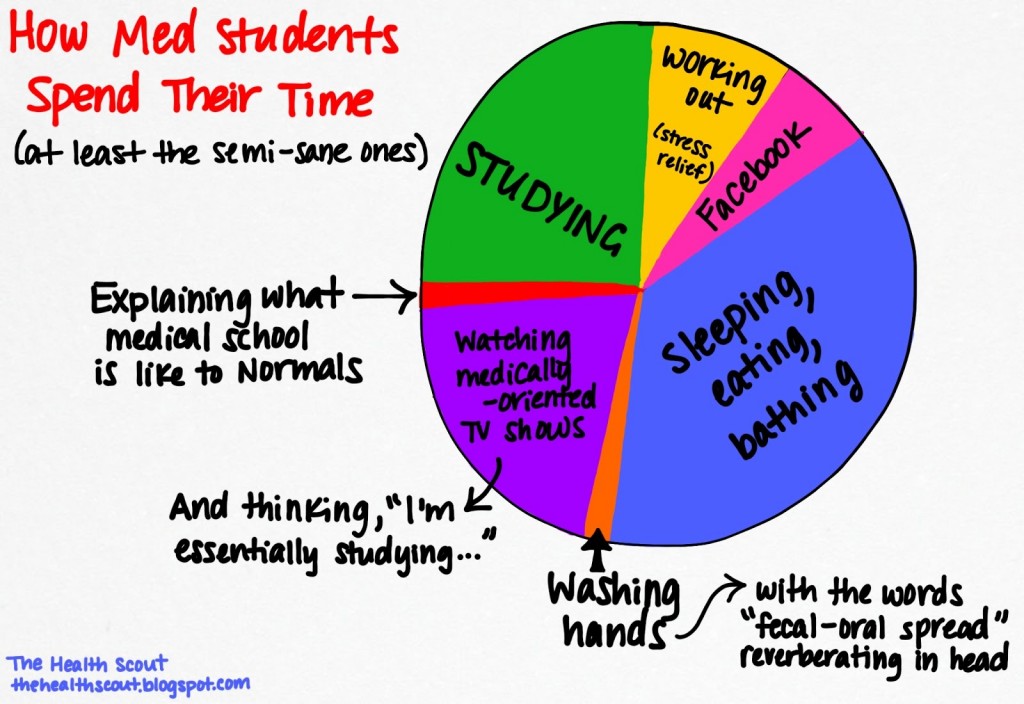

Most, if not all, doctors would agree that in order to keep sane, they’ve had to prioritize activities other than studying during their medical career. Often, it’s working out, cooking, sleeping, watching TV, or spending time with friends and family. It’s ultimately all about balance.

Being a medical student is like this: a teetering balancing act that may lean or sway more towards one activity or another on a day-to-day basis, but ultimately, in the big scope of things, stays firmly upright. This dynamic, rocking state of being is what balance truly is. I’m still awful at memorizing, and binder-loads of lecture material still catch me off guard. Yet, the biggest challenge of medical school has been learning how to best use the limited time I have in the most fulfilling way for me. It’s about learning to promote balance in my life.

In C. Dale Young’s poem, “Gross Anatomy: The First Day,” he begins the poem with an anatomy dissection instructor telling his students to:

“Begin with bone and muscle to discern exactly what you need to memorize. Each region has so many things to learn.”

He ends the poem with a snapshot of a sentiment too often felt by medical students:

“…You have many things to learn:

procedures, facts, new words at every turn.”

His introductory words elicit sighs.

Begin with bone and muscle to discern?

There is no time—too many things to learn.”

If I were to give advice to my naïve, pre-med self, I would sit her down and look her in the eye. I would tell her with confidence that she will be able to handle the course load of medical school just fine, that she will one day wield a stethoscope and call herself student-doctor without a second thought. But I would add, after motioning her to listen carefully, that she should make sure to pay particular attention to what is important to her. I would urge her to not let those things wither and to make finding balance a priority during medical school. Then I would share some sage advice I have gotten from fourth years past, “The extra hour you spend studying may not help you become that much of a better doctor in the long-run, but the extra hour you spend with your friends/your significant other/your family/your hobbies can make all the difference for your current and future happiness. Either way, you are going to get that MD. How you get there is yours to choose.”

2 replies on “Time | The Balancing Act of Medical School”

What I expected to be a rather sterile description of how to allocate personal time in medical school was actually a warm, beautiful read. Thank you.

Three years later and still a good, pertinent read. Congratulations–you’re almost there 🙂