Occasionally between lectures, some instructors will play music through the lecture hall sound system. As I sat waiting for the next lecture to begin, the Blues Brothers’ version of “Sweet Home Chicago” played. The Blues Brothers is one of my favorite films. I have a poster I purchased in high school that has traveled with me throughout my cross-country moves and still graces my bedroom wall today.

Occasionally between lectures, some instructors will play music through the lecture hall sound system. As I sat waiting for the next lecture to begin, the Blues Brothers’ version of “Sweet Home Chicago” played. The Blues Brothers is one of my favorite films. I have a poster I purchased in high school that has traveled with me throughout my cross-country moves and still graces my bedroom wall today.

Once the song ended, the class quieted down and the lecturer, Dr. Stephen Lurie, began. “How do you know this is blues?” He asked. Silence fell upon the class. “Blaring horns!” I said, breaking the silence with my excitement to be talking about the Blues Brothers in a medical school lecture.

Soon others piped in: “There’s a progression?” “Well the history of blues being connected to jazz…”

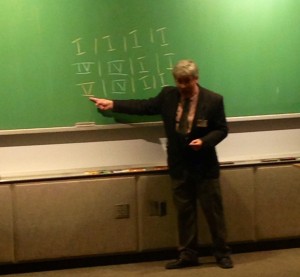

Soon, Dr. Lurie walked over to the lecture’s sound system and stated, “Well… let me play the song without any lyrics.” As the tune played on, he moved over to the board and drew a typical 12-bar blues progression:

Next, he played Louis Prima’s “Jump, Jive an’ Wail.“

“In this next song, you’ll see that if you bend the notes, put the melodies in different places, it’s jazzy” Cue: Gene Ammons’ “Red Top“.

Pointing to the same notes on the board- he moved as each song progressed. “People really couldn’t get away from this!” Cue: Nat King Cole’s “Route 66“

Cue: The Beatles “A Hard Day’s Night“

“Slow it down and you get…” Cue: The Clash’s “Should I Stay or Should I Go“

“You can also frame it and make people wait for it…” Cue: Dixie Chicks “Some Days You Gotta Dance” As soon as the lyrics “some days you gotta dance” began- he continued his routine of pointing to the different notes on the board.

Bringing this musical exploration to a close, Dr. Lurie urged us to see the power in the structure of the 12-bar blues. The journey that each song takes its listener on includes 4 bars establishing the root chord, a 9th bar with the climax, and a finale with the 11th and 12th bars of resolution. This format accommodates Gene Ammons’ jazz saxophone melody, Paul McCartney’s rock n’ roll vocals, and Mick Jones’ punk guitar riffs. Further, the very first note of a song has the very last note in mind and the song as a whole seeks to reach and entertain listeners through a collaboration with tools of the music industry. This structure enables listeners to focus on the uniqueness of each song which is highlighted by the forum of the 12-bar blues.

Bringing the lessons of these tunes into the wards, the structure of the oral patient presentation serves as clinicians’ 12-bar blues. The journey that each oral presentation takes its listener on includes a chief complaint, history of present illness, past medical history, and so on. This format accommodates the story of a patient with a simple otitis media to a patient suffering from Ebola virus. Just as with the tunes, the very first sentence of an oral patient presentation has the very last sentence in mind and the presentation as a whole seeks to provide proper patient care through collaboration with other healthcare professionals. This format enables any presenter and any listener to focus on the unique facts of each patient’s case, rather than different structural choices. As such, clinicians need not focus on creating a structure for their oral patient presentation, as it is already set in place. Rather, clinicians aught to focus on properly including the details of their patient’s story within the widely understood presentation structure.

One study that highlights the importance of the format of one’s oral patient presentation is “Expectations for Oral Case Presentations for Clinical Clerks: Opinions of Internal Medicine Clerkship Directors“. This article rates “organized systematically according to usual standards” as the most important component of an oral presentation and, “includes full review of systems” as the least important. Use the presentation structure and be efficient when including the information your patient has shared with you.

Lastly, Dr. Lurie urged the class full of medical students to remember that written presentations are short stories while oral presentations are live songs. With performance elements at our disposal, we must properly cater to our listener and create a masterful oral patient presentation should we wish to refine the art of healing- beginning with a well-tailored introduction. Reflecting upon his lecture, Dr. Lurie wrote, “I once had a saxophone teacher who was always after me to play fewer notes when improvising. ‘Anyone can play a lot of notes,’ he used to say, ‘but if you want to make music you should play only the good ones.’ Michelangelo was reputed to have said that his method of sculpting was to see the form hidden inside the block of marble, and then to carve away everything that was not part of that form. Of course, as a first-year student you are not always able to see that form, but as you practice giving oral presentations, that is the method I think you should be aiming at.”

Dr. Stephen Lurie now serves as a faculty advisor for the Medical Student Press. He served as Senior Editor for JAMA for four years. Read more about Dr. Lurie here.