“Call me Ishmael” is the first line in Moby Dick and probably the most famous opening line in all of American Renaissance era literature. Taken in a different context: “Call me Ishmael,” or perhaps: “My name is Ishmael,” could also be a first exchange between a doctor and patient. Coincidentally, our Ishmael in Moby Dick tells readers something that resembles what a patient might say to a doctor following initial greetings:

[So doc,] Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen, and regulating the circulation…whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.

So, translation? That is to say, can a physician translate Ishmael’s opening account into a chief complaint and past medical history? Here is my attempt: Ishmael is a middle-aged male (his age is not given) who complains about feelings of boredom and tiredness. He also describes a history of behavioral symptoms that suggest underlying feelings of anger. Ishmael mentions he looks for ways of “driving off the spleen”—the most fitting definition of “spleen” given by the Oxford English Dictionary is: “irritable or peevish temper.” Imagine now, if a patient used that exact phrase, “driving off the spleen,” to describe his anger and how he tries to rid it. As a student, I encountered patients during my preceptorships that mentioned similar behavioral symptoms including becoming “more irritable” and “losing their temper.” I found it challenging but helpful to imagine such feelings and consider them in the context of the patient’s chief complaint and past medical history. This allowed me to move with the patient’s sorry and avoid awkward moments and responses. As an exaggerated example, responding with a huge smile to a patient saying they’re “irritable” is not an ideal reaction and creates a difficult situation. Many times, these problems may not even be apparent until later reflection. To give students more chances to reflect, some medical schools such as Weill Cornell Medical College offer students recorded sessions of them interviewing mock patients. As a student, taking complete patient histories is not an easy task, and we can use all the practice we can get.

To wrap the above discussion into the ongoing theme of my posts—how reading imaginative literature is useful to doctors and scientists—I would suggest that my classmates, and also upper years and residents, make time to read poems and imaginative fiction that elicit a wide range of emotions. To this end, I can give the example that reading Othello and King Lear elicits very different emotional responses than reading, say, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and As You Like It. Yes, readers should read deeply into the variety of emotions in these plays, but they must remember to feel those emotions within the characters of Othello and Lear, or in our case, Ishmael and Ahab. This reading followed by feeling is a practice that physicians can use while taking a patient history: read and hear the patients’ situation, and then feel with the patient. Importantly, students and doctors can practice this even outside the clinic, while reading a poem, play, or novel.

Coming back to Melville’s novel, Ishmael announces his decision to go on a whaling journey at the end of Chapter 1: “By reason of these things, then, the whaling voyage was welcome; the great flood-gates of the wonder-world swung open.” Ishmael’s decision to “get to sea” then brings readers into Ahab’s infamously mad pursuit of the white whale.

My future posts will follow Ishmael’s narrative and bring to light elements that relate to medicine and science.

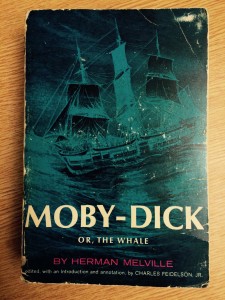

Featuring image:

Sea and sky by Theophilos Papadopoulos