Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.

– Margaret Mead

Doctors are at the forefront of society. They see the dark pits and abysses of humanity that the rest of us try to forget – those depths of despair that many of us will never experience.

As Medicine continues to change, so too does its definition of illness and what it means to be ‘sick.’ Illness means more than just a set of symptoms or a mark upon an X-Ray; it resides within the choices we make every day, the people we welcome into our lives and the jobs we labor for decades at a time. As medicine continues to encompass more and more of our everyday lives, so it takes on greater responsibility.

Advocacy was defined by Earnest et al. in the January 2010 issue of Academic Medicine as an ‘action by the physician to promote those social, economic, educational and political changes that ameliorate the suffering and threats to human health and well-being that he or she identifies through his or her professional work and expertise’ (3).

An article written in the 2014 edition of the AMA Journal of Ethics further divided the definition into two: agency which refers to working on behalf of a specific patient, and activism which is directed towards changing social conditions that impact our health (6). Although many doctors are comfortable with the direct care of their patients, what can often be forgotten is our social responsibility. Not only do we need to treat patients as individuals, but also as a group – as a community.

The doctor’s role goes beyond the hospital walls. The patient is not just the person sitting in the clinic, but the person next door, the young lady who goes to the shops, the schoolboy who drags his bag over his sullen shoulders every morning. Illness takes place in more than the patient’s body; it takes place in society, in the neighborhood, in the schools that cannot provide support and the families that can no longer cope.; what impacts our health? Is it a parasite within our bodies, a virus that has entered so far into our habitat? Or is it unemployment, poor housing, discrimination, social isolation, loneliness, and abuse? These types of vulnerabilities lead to much higher rates of both morbidity and mortality in those affected (4).

The doctor is the voice of those who do not have one. The status of the medical doctor has been respected throughout the centuries; the curer of ills, the bringer of life. While this is gradually changing in the new era of patient-centered care, it is still a prevalent idea.

The doctor should use this privilege and rank within society to fight for those who cannot. As a group, doctors can hold a lot of power within society. Here in the UK, several Royal Colleges have voiced their opinions in the mainstream media over a number of issues already; in 2015 the Royal College of Psychiatrists spoke out about the long distances many of their patients had to travel for support (8), while in 2013 the Royal College of Physicians highlighted the need to tackle obesity more rigorously (9).

These days it is much easier to be an advocate. All it takes is a few clicks on the laptop and you can enter into the sphere of social media. A quick search on Twitter will highlight numerous debates that are occurring amongst patients and doctors, nurses and pharmacists, families and politicians. The battle is no longer held in the debating arena, but within the public sphere.

There is another side to advocacy. Once one decides to expose themselves to the public sphere, they open the door to a hailstorm of criticism and disapproval. By stepping outside of their niche practice and showing their faces to the world, they invite a whole host of attacks. To counter such negative experiences, many medical organizations have offered advice for healthcare professionals who wish to take a bigger role within society.

For example, the Canadian Medical Protective Association (2) recommends doctors:

- Approach the issue with transparency, professionalism, and integrity.

- Work within approved channels of communication.

- Discuss concerns, suggestions, and recommendations calmly.

- Provide an informed perspective, and attempt to include the perspectives of patients and other healthcare professionals.

- Persuade rather than threaten or menace others.

- Remain open to alternative suggestions or solutions, and try to build on areas of consensus.

Another critique against advocacy is the question of the doctor overstepping her boundary. Is advocacy within the remits of the doctors’ role? There is after all a social contract between medicine and society; it is society that holds up the profession to the highest esteem, expecting them to abolish disease and alleviate suffering. A person does not take off their professional cloak the minute they leave the hospital grounds – rather, its presence can be felt in every setting, whether it be the local shop where they grab their newspaper or the primary school where they pick up their children; it is a type of respect that is rarely be found in other professions (4). Medicine and society are intricately linked, and to claim that the doctor’s job ends once the patient leaves the room is to be blind to the role of healthcare in people’s day-to-day lives.

Yet the role of advocacy is not a role that every doctor may wish to take on. Some doctors may fall into advocacy with burning desire to change the world, while others would prefer the calming atmosphere of the hospital room, with just themselves, their patient and a piece of paper in between. I believe advocacy was described best in 2011 when Dr Huddle, Professor of Medicine at the University of Alabama Birmingham, said that it “must remain an occasional and optional avocation in academic medicine, not a universal and mandatory commitment” (3).

On another level, we must be careful not to politicize medicine too far (5) – medicine is for the public and not just a puppet dancing on the strings of politicians. Medicine must speak for those who cannot, yet still maintain its autonomy. Certainly many of the issues that impact our health are heavily politicalized areas – from housing to employment to funding cuts. Doctors must be careful when speaking for their patients. They must not allow their words to become blinded by their biases. We must remember that the doctor’s duty is first and foremost towards her patients – to the public.

There are plenty of examples of advocacy out there –doctors who blog about the daily struggles of their patients, Twitter discussions about mental health and social care, and the clinicians who write books and articles pursuing public policies with an aim of building a more just, equal and ultimately healthier society.

So, how can you get involved? Grab a book, read a newspaper; join the debates on Twitter, pen an article, start a discussion – go out there and let your voice be heard.

Below are some examples:

- https://abetternhs.wordpress.com/

A blog written by a London GP. - https://juniordoctorblog.com/

A blog written by a junior doctor working in the UK. - http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/mar/29/drugs-talking-mental-health

An article written by Simon Wessely, President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists - Twitter accounts:

- @nhsconfed, NHS Confederation

- @TheKingsFund, Charity for Healthcare in England

- @HealthFdn, Healthcare Charity in the UK

- @RCPLondon, Royal College of Physicians

The Seven Social Sins:

Wealth without work.

Pleasure without conscience.

Knowledge without character.

Commerce without morality.

Science without humanity.

Worship without sacrifice.

Politics without principle.

– Gandhi, 1925 (7)

References

- Oxford Dictionaries. Advocacy [Online]. Available at: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/advocacy[Accessed: 4th January 2016]

- The Canadian Medical Protective Association. 2014. The physician voice: When advocacy leads to change [Online]. Available at: https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/-/the-physician-voice-when-advocacy-leads-to-change[Accessed: 4th January 2016]

- Kanter, S.L. 2011. On Physician Advocacy. Academic Medicine. 86:1059-1060

- Dharamsi, S., Ho, A., Spadafora, S., Woollard, R. 2011. The Physician as Health Advocate: Translating the Quest for Social Responsibility Into Medical Education and Practice. Academic Medicine. 86:1108-1113

- Huddle, T.S. 2011. Perspective: Medical Professionalism and Medical Education Should Not Involve Commitments to Political Advocacy. Academic Medicine. 86:378-383

- Freeman, J. 2014. Advocacy by Physicians for Patients and for Social Change. AMA Journal of Ethics. 16:722-725

- Easwaran, Eknath(1989). The Compassionate Universe: The Power of the Individual to Heal the Environment. Tomales, CA: Nilgiri Press.

- Buchanan, M. 2015. Mental health patients sent ‘hundreds of miles’ for care [Online]. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-33535864 [Accessed: 17th January 2016]

- BBC News. 2013. NHS obesity action plea by Royal College of Physicians [Online]. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-20878210 [Accessed: 17th January 2016]

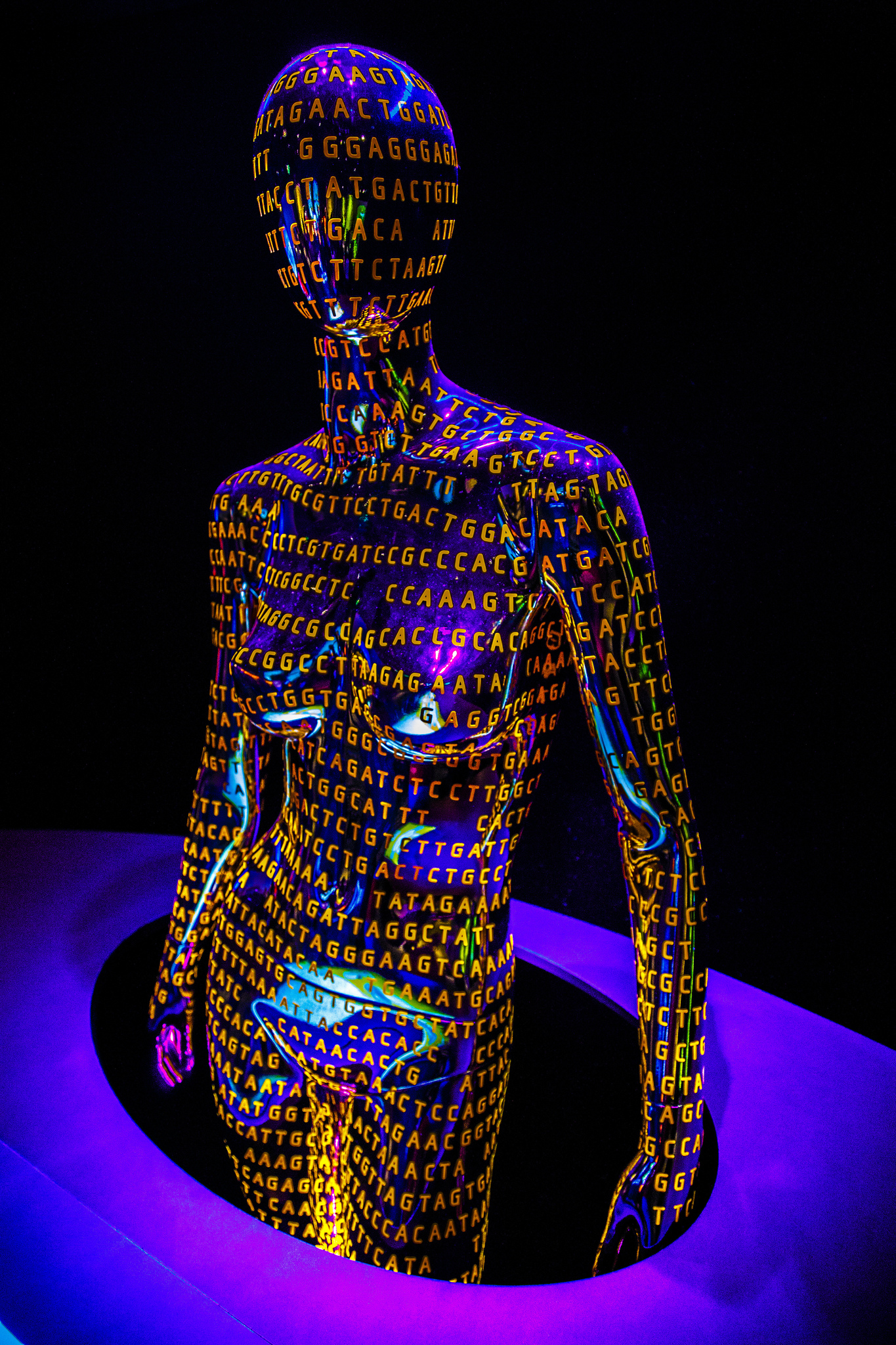

Featured Image:

Speak up, make your voice heard by Howard Lake