Valentine’s Day is not typically kind to medical students. While many couples share flowers and romantic dinners, my fiancé and I looked forward to escaping the hospital just long enough to exchange sweet-nothings over take-out sandwiches. Though lacking in outward displays of affection, this Valentine’s Day was imbued with something different. A few weeks ago, a patient taught me that love, it turns out, can exalt us and confound us, but it can also, literally, break our hearts.

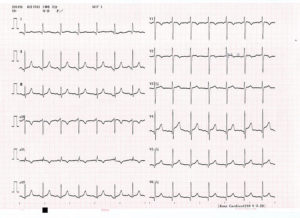

He was a thin man in his late seventies, a mop of unruly gray hair on his head. He came into the emergency room one evening, unable to catch his breath and complaining of severe chest pain. An EKG was rapidly obtained and showed concerning peaks and valleys of electrical activity. Troponin levels were rapidly increasing in his blood. TC, it appeared, was having a heart attack.

Though still in the early stages of my medical training, I knew what would come next. In rapid succession, TC would be rushed to the cardiac catheterization lab, and a stent would be placed in his coronary arteries, restoring desperately needed blood flow to his heart. He would recover. His loving wife and adult children would visit him in the hospital. In a few days he would return home.

I was wrong. Try as they might, TC’s doctors were unable to find any blocked arteries in his heart. With nothing to stent open, TC was admitted to the medicine ward for careful observation. Miraculously, his condition stabilized.

The next morning he was feeling better. Not wanting to forego his calisthenics, I found him walking along the bustling hospital corridor, pausing briefly outside each room to greet his fellow patients. As I corralled him back to his room for morning rounds, I couldn’t help but notice the gold wedding ring hanging from a length of frayed twine around his neck. He caught my gaze and smiled, “pretty, isn’t it?”

Lowering himself carefully to his bed, he explained why he no longer wore the ring on his finger. His wife, he lingered on the word, had died almost three months ago. His children, long since grown, had come home for a while, but were now back to their own lives. He’d considered moving into a smaller place—less lonely he figured—but he couldn’t bear the thought of discarding any of her things.

Later that day, TC went for an echocardiogram which immediately revealed his diagnosis.

He had Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also known as “broken heart syndrome.” It is a rare condition, but strikes most commonly after a period of great emotional turmoil. Marked by chest pain and shortness of breath, the initial presentation is not at all dissimilar to a heart attack, so committed in its mimicry that the EKG and blood findings are often identical.

Although the pathogenesis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is not completely understood, it is postulated that adrenaline, released in times of great emotional distress, may overwhelm and eventually damage the heart. With enough damage, the heart breaks, contorting itself into a characteristic shape—wide at the bottom with a distinctively narrow neck. The shape resembles a Japanese takotsubo pot, a vessel historically used to trap octopus.

As a trainee in the field of medicine, my classroom preparation taught me to be objective—to plumb the pertinent facts of a patient’s history and physical exam in order to provide effective treatment. But it is patients like TC who teach me that good doctoring requires something more. Though less tangible, it is clear that one’s physical and emotional well-being are inextricably linked.

Several days later, heart ostensibly healed, TC was ready to return home. He stepped into the elevator, turned, and waved goodbye. A gold ring shone brightly on his finger.

Photo credit: Chandrahadi Junarto