Back in May, I attended the 2016 American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) Annual Scientific and Clinical Meeting in Washington, D.C. On my first day, I watched Dr. Annette E. Fineberg, a board certified obstetrician and gynecologist from Sutter Davis Hospital in California, present a short film on upright vaginal breech delivery. The movie featured a woman at term deliver in the operating room by resting on all fours on her hands and knees. She swayed her bottom from side to side in order to promote fetal descent and as a way to cope with pain, as she did not receive an epidural. The baby crowned, bottom first, and then slowly spontaneously delivered its legs, trunk, arms, and finally, head. A successful vaginal breech delivery (VBD)!

Ever since watching that amazing film, I have been interested in reading and talking about VBDs. But on the residency program interview trail, I have begun to notice a trend that some providers seem to have strong, negative attitudes regarding VBDs of singletons. One person even glared and incredulously responded, “No one in the country does those.” I think Dr. Fineberg and the other clinicians I have met that do would disagree.

But I do wonder why providers feel so strongly about a particular position regarding more controversial topics in reproductive health. In regards to vaginal breech delivery, I think that a big prejudice is the absolute horror stories every seasoned OB/GYN has to tell about the time they saw a baby’s head get stuck. These accounts are upsetting, sad, and help explain why someone might think me ridiculous for even asking about training in vaginal breech delivery.

The most common response, though, that I receive is something like, “We don’t do those. But you will probably not find many programs that do since ACOG does not recommend vaginal breech deliveries.” This reply is less emphatic and more accurate if following the 2001 ACOG committee opinion, which states, “planned vaginal delivery of a term singleton breech [is] no longer appropriate.”1 The reasoning in 2001 was largely based on results from the Term Breech Trial, a large, multi-institution, randomized control trial comparing planned vaginal birth with cesarean deliveries for term singletons with breech presentation. This study indicated that neonatal morbidity and mortality significantly increased with vaginal breech versus cesarean section delivery.2

Since the 2000 Term Breech Trial, clinicians have begun to question if vaginal breech deliveries should have a strict ban. Instead, there is evidence suggesting that vaginal delivery is a safe option in select women with breech presentation. The authors of the Term Breech Trial performed two prospective studies in which they examined maternal and child outcomes at both 3 months and 2 years post-partum. At two years post-partum, there was no longer a difference in mortality nor neurodevelopmental delay in the children born by vaginal breech delivery versus cesarean section.3 Retrospective studies with specific protocols similar to those described in the Term Breech Trial have shown excellent neonatal outcomes for vaginal breech delivery of term singletons.4-6 In 2015, Berhan and Haileamlak published a meta-analysis of 27 articles with a total population of 258,953 women comparing the morbidity and mortality of term singleton breech mode of delivery between 1993 and 2014. While the relative risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity was 2-5 times higher in planned vaginal delivery versus cesarean, the absolute risks of several variables, including perinatal mortality (0.3%) and fetal neurologic morbidity (0.7%), were low.7

In the updated committee opinion on vaginal breech delivery published in 2006 and reaffirmed in 2016, ACOG states that “planned vaginal delivery of a term singleton breech fetus may be reasonable under hospital-specific protocol guidelines for both eligibility and labor management.”8 The Royal College of Obstetricians, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada report similar recommendations.9-11 According to the ideal candidate for a term, singleton vaginal breech delivery is the following:12-14

- Frank or complete breech presentation with flexed or neutral head attitude;

- Estimated fetal weight between 2500 and 4000 grams;

- A patient willing and comfortable with a trial of labor;

- Clinically adequate maternal pelvis.

Contraindications to vaginal breech delivery are categorized as a fetal, maternal, or provider factor:12-14

Fetal Factors

- Incomplete breech;

- Hyperextended neck;

- Cord presentation;

- Fetal growth restriction or macrosomia;

- Congenital anomaly incompatible with vaginal delivery (e.g. thyroid mass).

Maternal Factors

- Patient unwilling to attempt/uncomfortable with a trial of labor;

- Clinically inadequate maternal pelvis;

Provider Factors

- Lack of operator experience.

Obstetrics governing bodies agree that external cephalic version—whereby a provider uses their hands on the abdomen to rotate the fetus in utero from breech to vertex presentation—should be recommended and attempted first before considering vaginal breech delivery. And all leading sources recommend that an experienced provider needs to be leading the delivery.

But if there are few opportunities in residency to practice vaginal breech delivery, how will there BE any future providers who qualify as experienced?

First and foremost, I hope to enter a residency program that provides me with the training I need to be a competent women’s health provider. But I also intend to seek training in vaginal breech deliveries, whether it is via simulations—which RCOG notes is an appropriate way to build experience 9—or via an elective at another institution where there may be further opportunities. My goal is twofold: (1) offer the best individual options for mode of delivery to my future patients; and (2) help lower cesarean section rates in the United States. Hopefully, I will get the right match!

References

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No.340: Mode of Term Singleton Breech Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jul;108(1):235-7.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, and Willan AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375-1383.

- Whyte H, Hanna ME, Saigal S, et al Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group, Outcomes of children at 2 years after planned cesarean birth versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: the International Randomized Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:864-871.

- Guiliani A, Scholl WM, Basver A, Tamussino KF. Mode of delivery and outcome of 699 term singleton breech deliveries at a single center. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1694-8.

- Alarab M, Regan C, O’Connel MP, Keane DP, O’Herlihy C, Foley ME. Singleton vaginal breech delivery at term: still a safe option. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:407-12.

- Borbolla Foster A, Bagust A, Bisits A, Holland M, Welse A. Lessons to be learnt in managing the breech presentation at term: An 11-year single-centre retrospective study. Autralian and New Zeland Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2014;54:333-339

- Berhan Y, Haileamlak A. The risks of planned vaginal breech delivery versus planned caesarean section for term breech birth: A meta-analysis including observational studies. BJOG 2015: DOI; 10.1111/1471-0528.13524

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No.265: Mode of Term Singleton Breech Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Dec;98(6):1189-90.

- Guideline No 20b: The Management of Breech Presentation. Oxford: RCOG, 2006.

- Kotaska AK, Menticoglou S, Gagnon R. SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline No. 226: Vaginal Delivery of Breech Presentation. JOGC. June 2009.

- RANZCOG, Cobs-11: Management of the Term Breech Presentation. Melbourne: RANZCOG, 2009.

- Hofmeyr JG, Lockwood CJ, Barss VA. Overview of issues related to breech presentation. UpToDate: Accessed 10/11/2016

- Hofmeyr JG, Lockwood CJ, Barss VA. Delivery of the fetus in breech presentation. UpToDate: Accessed 10/11/2016

- Secter MB, Simpson AN, Gurau D, et al. Learning from Experience: Qualitative Analysis to Develop a Cognitive Task List for Vaginal Breach Deliveries. JOGC 2015

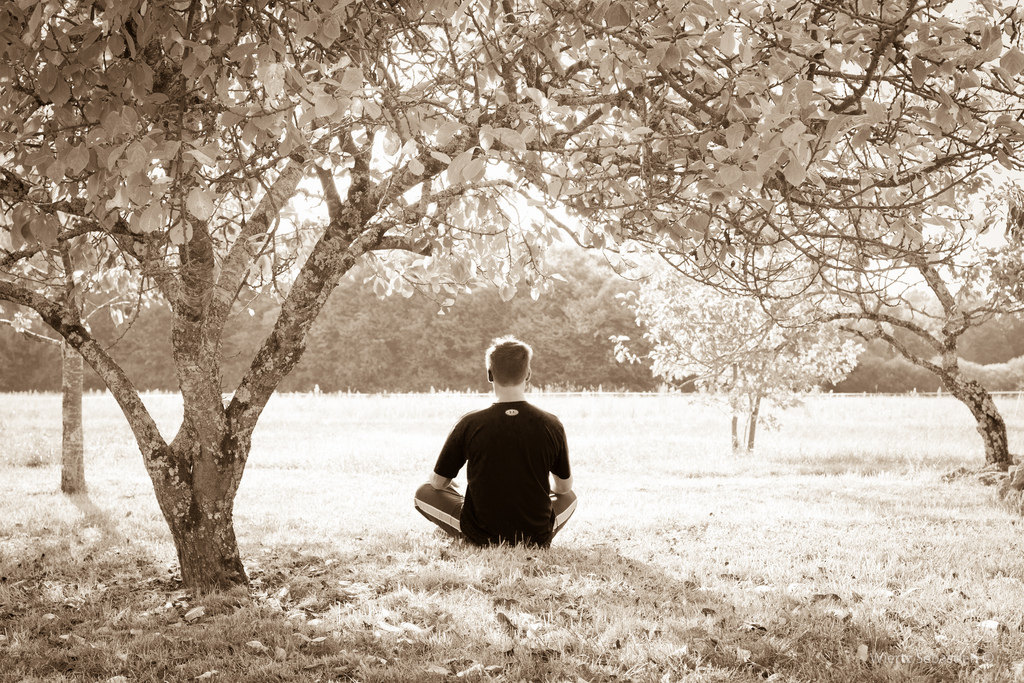

Photo credit: MIKI Yoshihito