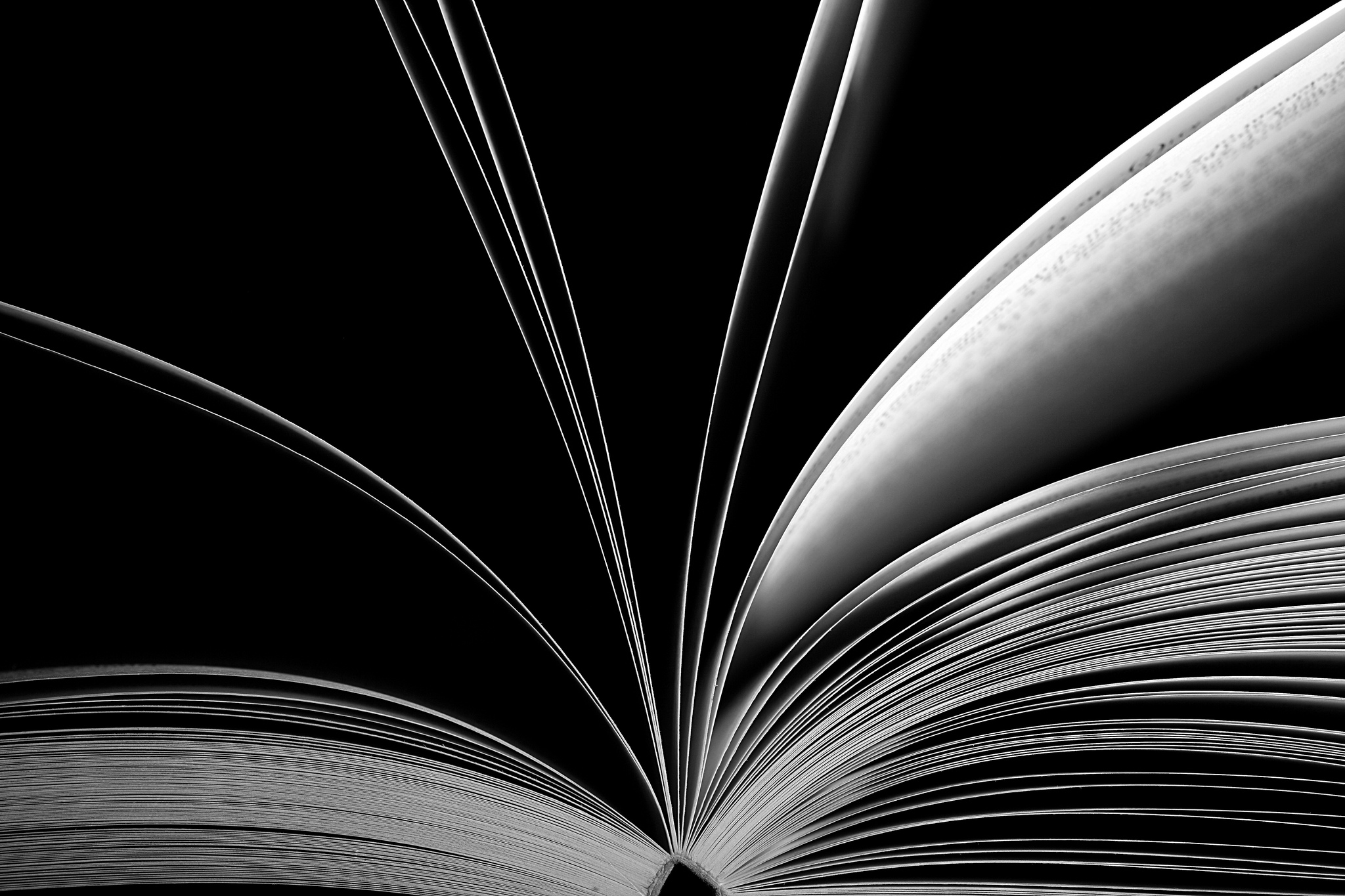

What is the usefulness of imaginative literature to the practice of medicine and science? This question continues to intrigue me, and according to Weill Cornell’s admissions dean Dr. Charles Bardes, it is an important question that “remains unanswered.” I approached Dr. Bardes in mid-November this year after being impressed and intrigued by the physicianship lectures he gave as part of our first-year Essential Principles of Medicine curriculum. One of his most memorable lectures was the October 9th presentation on how to take vital signs. His lecture started out with an introduction to taking body temperature. As many readers know, body temperature is often measured first when vital signs are being taken, and it’s one of the easiest measurements to take. But the meaning of a particular body temperature is not always so simple. In the course of his lecture, Dr. Bardes reminded students of the possible meanings of an increased or decreased body temperature relative to the average normal range. He then proceeded to explore one interpretation of a decreased body temperature: dying and death. He presented a historical (Socrates) and a literary (Falstaff) example of decreased body temperature as it relates to dying and death. Importantly, how Dr. Bardes chose to explore this relation was more interesting than what he chose (though I do share with Bardes a common fascination with the character of Falstaff). I quote, below, from his October 9th lecture:

Here you see a representation of the death of Socrates, as narrated by Plato, and painted by David. And the text describes how Socrates, after drinking hemlock—he’s just about to do so here—becomes cold. And he becomes cold beginning with his feet, and it gradually ascends up his body, and Plato says that when the cold has reached the level of the thorax, that’s when Socrates breathed his last. You can see here a combination of biologic observation, that is, that this sort of ascending coldness does in fact occur, but also a little bit of literary fiction—there’s nothing magical that when the cold reaches your chest, you die; that was another little bit of medical folklore. [Also] Here we have the death of Falstaff, which actually happens offstage in the play, but onstage in the Laurence Olivier movie, and Mistress Quickly describes how Falstaff becomes cold, ascending from toe to chest, until he is, in her words, as cold as any stone. Those are the meanings of…decreased temperature.

Certainly, there are numerous ways to provide details and anecdotes on how changes in body temperature are related to changes in physiology. A keyword search in PubMed of “body temperature changes” reveals more than fifty-thousand articles on that subject. Dr. Bardes didn’t choose this path to present his lecture. Yes, one can learn a great deal about body temperature changes by reading any of the articles on PubMed, but what do such articles on case studies and molecular pathways not tell us? They don’t provide the human and historical context to the medical condition. Yes, case studies no doubt can include anecdotal material, but such material provides a limited perspective. What about the vast historical and literary contexts that are available to us? Why should we not look through such material and mine them for gems related to our subject matter? Socrates in human history experienced death and dying, as did Falstaff amongst Shakespeare’s universe of characters. Dr. Bardes wonderfully brought in such contexts to give each of us diverse tools to make meaning, and to quote again from the lecture: “these things [increased and decreased temperature] have meaning. Why do we do them, because they have meaning.” How we make meaning, then, and the tools we choose to do this, is up to us.

I continue, every day, to explore literature, medicine, and science; for me, they are just variations of the same thing: a desire to better understand and describe life, and to make meaning in life. Though the methods and jargon differ between those fields, their objectives should be common and coherent. If the objective, then, is to make meaning in life, then each field ought to be practiced daily with the same enthusiasm and joy we give to life itself. I practice all three–literature, medicine, and science—daily and with joy because I have fallen in love with all three. The best works in all three fields have been produced when their creators have fallen in love with their works, a cliched but true notion (on this note, I’ll cite Josh from the new-age Broadway musical I recently saw, If/Then, when he affirmed to viewers that “it’s cliche, which means it’s true”—indeed, it’s true that the best works were created by those who loved what they were creating). On this theme, the late Yale poet and professor John Hollander said this of Professor Mark Van Doren’s sublime book on Shakespeare, that he “enlightens us, not because he has any special knowledge or private advantages, but because his love of Shakespeare has been greater than our own.” A love of making meaning in life, then, I propose, will be found in the greatest physicians and physician-scientists, because they will produce the best works when they love what they do. I will, on this note, go out on a limb to surmise that if Falstaff had been trained as a physician, and not as a knight, he would have been an excellent doctor, though he clearly—and we love him for this—fails in his duties as a knight. He loves living, however, and making meaning as he lives. Harold Bloom, most certainly our best reader of Shakespearean in the last half century, said this of Falstaff, that “if you crave vitalism and vitality, then you turn…most of all to Sir John Falstaff, the true and perfect image of life itself.”

For The Medical Student Press, I have two main objectives I hope to achieve in my blog posts. Like Dr. Bardes, I’d like to share how reading imaginative literature, focusing on Shakespeare, has provided contexts and insights for my medical training. Secondly, and this will simply be an extension of my first objective, I’d like to share my enjoyment of literature, medicine, and science with colleagues and readers. In this manner, I’d like to fill what I think is a gap in the medical humanities canon. There has already been much written about medicine and medically-related themes in poetry and fiction, but such pieces seem too literary and theoretical for my taste. Another category of writing within the so-called field of medical humanities involves poems or short stories that seek to communicate personal anecdotes in medicine or reflect upon them. But there is a third category of writing, one that I think has been under-appreciated, and the goal for these writers is in describing the relevance and usefulness of imaginative poetry, fiction, and drama to scientists and physicians. This relatively unexplored third category is what interests me and what I like to write and think about. I end this post by echoing what Weill Cornell’s Dean Laurie Glimcher shared with us in her holiday greetings:

Do not go where my path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail. -Ralph Waldo Emerson Warm wishes for the holidays, Laurie H. Glimcher, M.D. Stephen and Suzanne Weiss Dean

Fetured image: and read all over by Jonathan Cohen

I watched as any sliver of hope vanished from their eyes. They would not wake up from this nightmare. The moment my mentor delivered the diagnosis, I could feel the world take a 180 eighty degree turn for this family. It was as if their world froze at that moment. How could this be? The child looked so peaceful, fast asleep while hospital monitors blinked around her. Just a week ago, they were running around to sports practices and dentist appointments and going through the everyday motions that we consider to make up a normal life. I’m not even sure that this family was breathing at this moment. The room became deafening silent as all the color drained from their faces. The doctor proceeded to talk about what would happen in the days to come. What did this mean for their child?

I watched as any sliver of hope vanished from their eyes. They would not wake up from this nightmare. The moment my mentor delivered the diagnosis, I could feel the world take a 180 eighty degree turn for this family. It was as if their world froze at that moment. How could this be? The child looked so peaceful, fast asleep while hospital monitors blinked around her. Just a week ago, they were running around to sports practices and dentist appointments and going through the everyday motions that we consider to make up a normal life. I’m not even sure that this family was breathing at this moment. The room became deafening silent as all the color drained from their faces. The doctor proceeded to talk about what would happen in the days to come. What did this mean for their child? So much of early medical education involves pouring over books and PowerPoints, trying to memorize as many details as possible. It is important to have that foundation of knowledge, but what I have come to realize is that there are rarely pure “textbook cases” because so much more goes into caring for a patient. One size does not fit all in medicine. This experience brought back the humanity of medicine. I witnessed how knowing and understanding patients enables a physician to be an advocate for their patients, a role I consider to be the most important of the many roles a physician takes. I can never come close to knowing exactly what these families are going through. I also can’t thank them enough for allowing me to be present during their most vulnerable moments, for taking time to talk with me for a brief period to get a glimpse of their journey. Ultimately, this experience was a reminder that the art of medicine can’t be discovered in textbooks. It is learned from our patients and the uniqueness that their individual journeys bring to each patient encounter.

So much of early medical education involves pouring over books and PowerPoints, trying to memorize as many details as possible. It is important to have that foundation of knowledge, but what I have come to realize is that there are rarely pure “textbook cases” because so much more goes into caring for a patient. One size does not fit all in medicine. This experience brought back the humanity of medicine. I witnessed how knowing and understanding patients enables a physician to be an advocate for their patients, a role I consider to be the most important of the many roles a physician takes. I can never come close to knowing exactly what these families are going through. I also can’t thank them enough for allowing me to be present during their most vulnerable moments, for taking time to talk with me for a brief period to get a glimpse of their journey. Ultimately, this experience was a reminder that the art of medicine can’t be discovered in textbooks. It is learned from our patients and the uniqueness that their individual journeys bring to each patient encounter.