‘Back in elementary school, I realized we all have a genetic, lethal disease called aging. I remember being frightened that my mother would die and terrified that my existence was ephemeral and meaningless. At the time, it felt like I was being told I had terminal cancer or some other horrible disease. Death was inevitable. No matter how rich or successful I could be in life, it would all be lost in the end. So, still a child, I found an objective, a purpose for my life: to cure human aging.’

Joao Pedro de Magalhaes (1)

Of all the diseases we have left to conquer, one raises its voice above all others: the disease of aging. From anti-wrinkle creams to advertising billboards, from our conceptions of beauty to our desire for youthful skin, our fear of aging is present in all walks of life.

But is aging a disease? Is it a demon that must that be conquered, lurking beneath our skin, crumpling up our genes until our skin sags and our hair turns grey? Or is it a natural part of life – something that needs to embraced with humility? Is our preoccupation with aging a cultural phenomenon, a type of ignorance or obsession that needs to be tackled by changing social attitudes, or is it primarily a problem of medical science?

Eternal Youth vs Immortality

What is it that we are actually fighting for – do we want to live forever, or do we want to be forever young? Most of us would not wish to live a longer life if it meant we continued to age. What we long for is a good quality of life while still holding on to more years. This is best highlighted in the Greek myth known as Tithonus Error. Tithonus was a mortal who was granted immortality by Zeus but was not granted eternal youth. As a result, Tithonus became increasingly debilitated and demented as he aged (2). This is a fate no one would wish to have. The quest, it seems, is to extend one’s years upon this earth while retaining quality of life, looks, and independence. If this is so, we must ask ourselves: is this something worth fighting for?

One argument against the idea of ‘fighting aging’ is the concept that aging is a natural process. For those making this argument, the insistence on limiting aging is uncomfortable; who are we to go against nature? In fact, some would even argue that it is aging that makes us human. Indeed, without the knowledge of mortality placed upon our fragile shoulders, we would never value those things which are so important in our lives and yet so transient – our first kiss, our first day at school, our first date. If we were to extend our lives infinitely, then the value of the present moment may disappear.

As emotively tempting as this argument may be, if one takes a step back and takes a look at the history of medicine, one begins to see that battling nature is something that science has always done; from antibiotics to vaccinations, from the eradication of smallpox to the application of technology, fighting the natural world is an inevitable component of science. Indeed, battling the features of aging makes up a large part of modern-day medicine; we battle stroke and heart disease, insidious cancers, and debilitating degenerative diseases every day within our hospitals and with our surgeries. What makes ‘fighting aging’ any different?

The Cultural Phenomenon

This question ultimately goes back to the cultural phenomenon of aging. Aging is a rather new phenomenon. At the beginning of the 20th century, only 5% of the population was over 65 years of age, while today people are able to lead active and independent lives well into their 90s (3). With this rise in aging has come new prejudices and stereotypes. It has been argued that our negative attitudes against ageing emerged relatively recently, in the 18th century. Prior to this era, the elderly were often held in high regard, seen as carriers of wisdom and knowledge thanks to their years upon this earth. But as more and more people began to survive into their 80s and 90s, the idea of being a ‘nuisance’ began to take hold. Employers felt that the elderly were holding on to jobs that could be taken over by the “young and fit.” This change in attitude is reflected in our vocabulary with words such as ‘codger’ (meaning an odd, old fellow), and the change in meanings of certain words over time, such as ‘fogey’, which previously meant a wounded war veteran but now is used more pejoratively to describe those who are old and thought to hold ‘old-fashioned’ views.

The social role of the elderly has changed dramatically as well. With fewer multigenerational families living under one roof, the role of the elder within the family structure has been lost (3). This gradual change in society is reflected in the way we view age. We equate youth with beauty and aspire to look as young as possible. Yet on a grander scale, the way we view age has also corresponded to a larger shift in our society’s policies, in our public expenditures, and in our healthcare.

Within medical care, conditions such as depression are often ignored in the elderly and often seen as a part of aging itself. From a social perspective, discrimination in social care is evident in the assumptions that people may have about how older people should live their lives and what constitutes a life worth living for the elderly. On a public health level, there is a strong suspicion that the use of Quality Adjusted Life Years, a tool used in the UK to assess the costs of treatments, will often discriminate against treatments for diseases such as Alzheimer’s Disease, Osteoarthritis and Age-related Macular Degeneration, most of which would mainly benefit older people with few remaining years. Within the research sphere, the elderly are often excluded from clinical trials, with this under-representation of the elderly affecting the number of available treatments for them. Most importantly, from the patient’s perspective, older people are more likely to feel talked over compared to other patients when they are in the hospital, often feeling ‘as if they weren’t there’ (5). All of these examples illustrate how our culture of youth has manifested itself within the sphere of medicine, where it is our responsibility to be non-judgemental. Yet this is the world in which we live. If we want to make a change, we must become aware of such uncomfortable realities and understand what has given birth to them.

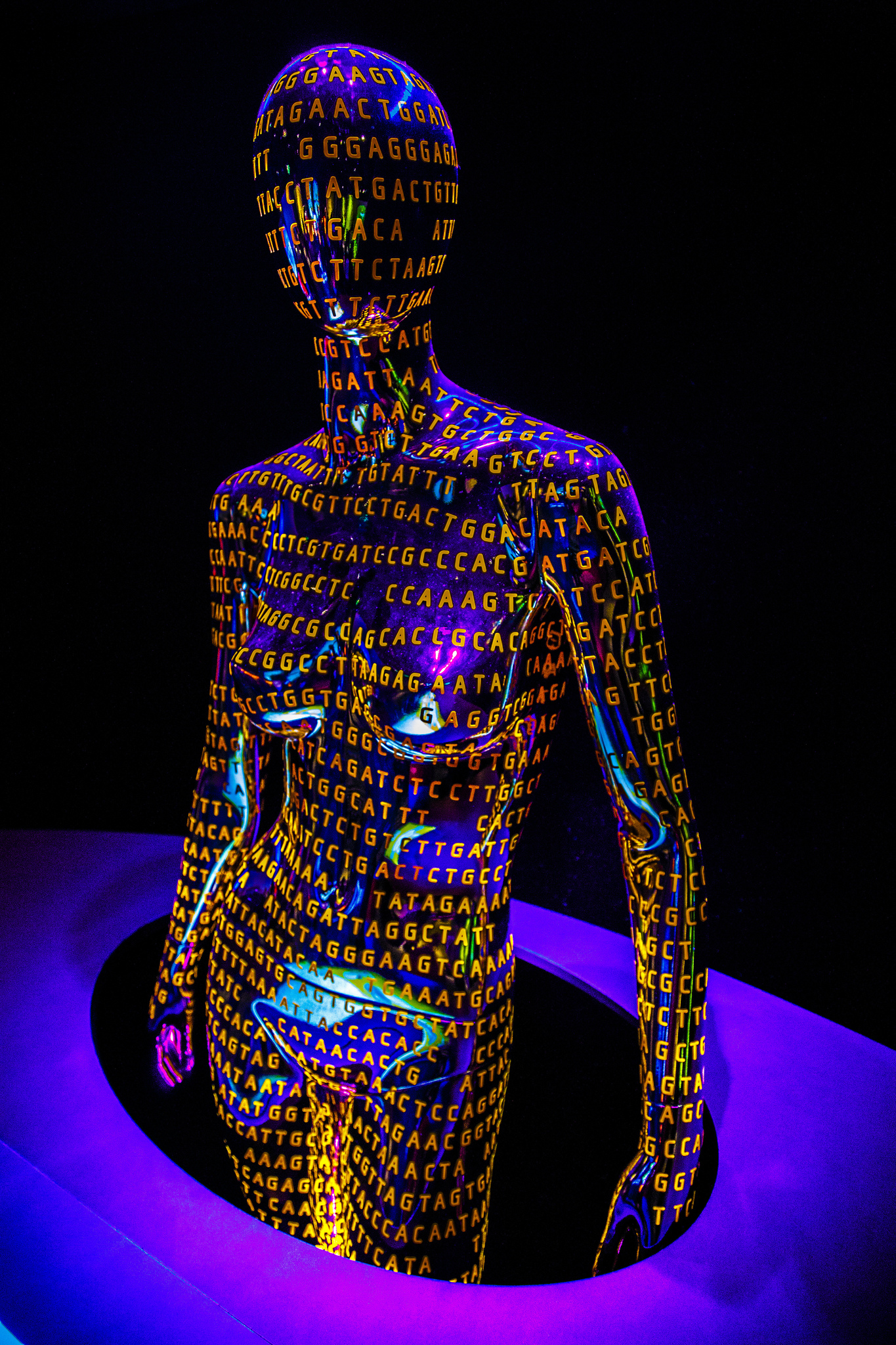

Even if we wish to view aging as a biological phenomenon, for example by looking for “anti-aging” genes within our laboratories and for drugs that can reverse the damage done to DNA over time, we still have to take into account society’s perception of the elderly. We still have to ask the difficult, philosophical questions. For example, are we battling aging because it will allow us to be healthier and have more fulfilling lives, or because of our modern obsession with youth and beauty? Likewise, how would we evolve or change as human beings if we were able to slow, stop, or even reverse the process of aging?

Perhaps conquering aging is not the same as vanquishing cancer, for growing old is an intricate and natural part of our lives. Indeed, perhaps it is part of what makes us human. These are questions that no one person can answer, and which need to be debated within the public sphere. The discussions that arise from asking these questions will undoubtedly impact the direction medicine takes with respect to its interaction with aging; maybe more resources will be dedicated to ‘diseases of the elderly’. If we are lucky, maybe this will all cultivate an attitude of acceptance and empathy within a culture that sees aging as a part of life. Maybe we can change a culture. Maybe we can even save a life.

“We have added years to life; it is time to think about how we add life to years.”

Robert Kennedy (6)

References

- Magalhaes, J. P. Fearing Death and Curing Ageing [Online]. Available at: http://www.senescence.info/death_and_aging_fears.html [Accessed: 14th September 2016]

- Magalhaes, J. P. Should we cure Ageing? [Online]. Available at: http://www.senescence.info/physical_immortality_myths.html [Accessed: 14th September 2016]

- Big Picture. 2014. Ageing and Society [Online]. Available at: https://bigpictureeducation.com/ageing-and-society [Accessed: 30th September 2016]

- Jones, R. 2007. A Journey through the Years: Ageing and Social Care. Ageing Horizons. 6: 42-51

- Centre for Policy on Ageing. 2009. Ageism and age discrimination in secondary health care in the United Kingdom. Department of Health.

- Steinsaltz, D. 2016. Become the New 60;. Nautilus; 36 [accessed 28th May 2016]. Available from: http://nautil.us/issue/36/aging/will-90-become-the-new-60

Featured image:

Age by Iburiedpaul