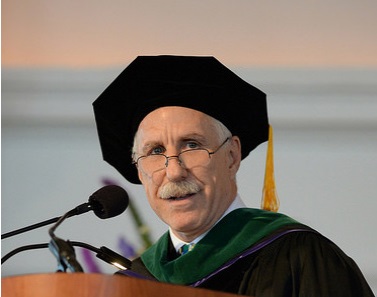

Good afternoon, and thank you for inviting me to be your speaker today. My name is Paul Rothman, and I am the dean of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the CEO of Johns Hopkins Medicine. It’s my privilege to be here on this memorable occasion to celebrate you, the esteemed graduates of the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Class of 2016.

First, I want to say congratulations. You should be incredibly proud of yourselves. You have succeeded in one of the country’s most prestigious and rigorous programs, which is a testament to your immense talent, intelligence and drive.

Whether you are moving on to a residency, a postdoc, a job in industry or another professional stepping stone, today opens up great possibilities for you. You are forging ahead in an era of unprecedented opportunities in science and medicine.

In 2016, we are on the verge of some astounding breakthroughs, thanks to increasingly sophisticated medical imaging tools, next-generation gene sequencing, computational modeling, and other technologies that allow us to obtain and analyze complex data sets.

I started my career in 1984, when our work as medical professionals was far different than it is today. Over the past 30 years, I have had the pleasure of witnessing stupefying advances in medicine—progress that has had enormous impact on how we diagnose disease, deliver health care and conduct health-related research.

The rate of progress should be even more stunning during your careers. Soon, your whole genome is going to be accessible on your iPhone. An EKG will be self-administered at home with a hand-held device, and an iWatch will monitor seizure activity. Highly accurate autonomous robots will assist surgeons in the OR. And health behaviors will be tracked so closely that we will know in real time whether patients are adhering to their treatment regimens. There’s no doubt that technological innovation will save many, many lives.

Which raises the question, as I look out at all of you newly minted doctors: What is the role of the human doctor in this brave new world of medicine, which threatens to reduce the patient to a data set and “doctoring” to an algorithm? How can we harness the power of technology without undermining the doctor-patient relationship?

I recently read a striking study by an assistant professor of medicine here at Northwestern named Enid Montague. She used videos to analyze eye-gaze patterns in the exam room and found that doctors who use electronic health records spend roughly onethird of each visit staring at the computer. Not only is that alienating, but it can mean that we doctors aren’t picking up on important non-verbal cues from our patients.

And the more sophisticated our medical technologies get, the more potential there is for this distancing effect. For example, a hand-held ultrasound is more precise than a traditional physical exam—be it percussing a patient’s abdomen to determine the size of the liver or putting a stethoscope to someone’s chest to listen for abnormal heart rhythms.

But the human touch is an important part of building trust between doctor and patient. Can you imagine a scenario in which a doctor did a physical exam without once actually laying hands on the patient?

I like to argue that technology serves to get the unneeded variation out while the physician is there to keep the needed variation in health care.

The computer can ensure that the diagnostic process is efficient and thorough, with all potential diagnoses considered. But the physician must be there to help interpret findings or to say, maybe that patient can’t afford that drug, or that treatment regimen is too complex for that patient to manage. We as human doctors can factor in so many subtle observations and make an appropriate judgment call.

In order to do that, we need to listen. William Osler, one of Johns Hopkins’ founding fathers, is famous for saying: “Listen to your patient. He is telling you the diagnosis.” And I would take this opportunity today to echo that advice to all of you.

Here’s the thing: I believe that most of us who go into this field start out compassionate— motivated to help our fellow humans and relieve suffering. I can tell you that’s what drew me to medicine, and I’m sure the same is true for you.

It used to be we would train residents out of this inclination to be humanistic—through impossibly grueling hours and a culture of browbeating. When my wife and I trained, we worked more than 100 hours a week, and it took us years to start feeling human again after that.

Fortunately, I believe medical schools have made great strides over the past decade in nurturing empathy. We’ve changed our selection criteria to attract more caring, well-rounded people, and our residents are now limited to a somewhat more humane 80-hour workweek.

The problem is that in trying to teach our trainees to be more humanistic, we’re going against the grain of society. In 2016, efficiency is the name of the game, so doctors’ visits and hospital stays are growing shorter, making it harder to form meaningful relationships with our patients. Furthermore, so much of our communication today is now mediated through technology. Think about it: People vet potential mates through online dating sites. Friends stay in touch over Facebook. We communicate with our officemates via email.

Health care is a service industry, so look at other service industries and you’ll see a trend of dramatic depersonalization over the past couple of decades. When was the last time you spoke to a human while making a travel reservation or depositing a check? I just read that Wendy’s is adding self-service ordering kiosks to all its restaurants this year. For better or worse, DIY gene testing is already on the scene. As younger generations enter the workforce, this trend will only intensify.

But here is the really good news about your generation, and this gives me a lot of hope. Even though millennials have been raised on technology, study after study shows that your generation is more community-minded than the Gen Xers and baby boomers who preceded you.

You’re more likely than previous generations to state that you want to be leaders in your communities and make a contribution to society, and roughly 70 percent of people your age spend time volunteering in a given year. Not only do you all have the idealism of youth, but you’re also matching that idealism with action. And it’s inspiring.

At Johns Hopkins, all our trainees participate in service projects, and I suspect that’s true for most of you as well—whether it’s providing free hepatitis B screenings for community members in Chicago’s Chinatown or donating your time to CLOCC, Northwestern’s Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago Children. In my view, the very best physicians are those who possess a service ethos—who are not just humanists, but humanitarians.

Recently, I was helping my daughter with her medical school applications, and one of the essay prompts included this quote from the late Nobel Laureate George Wald: “The trouble with living with contradictions is that one gets used to them. The time has come when physicians must think not only of treating patients but also of trying to help heal society, if only so that their work is not incompatible with … surrounding circumstances, partly of their own making.”

Let’s unpack that quote.

In American cities, long-standing systemic inequities mean that many members of our communities lack access to adequate health care, decent schools and other advantages that many of us here today take for granted. What Wald is saying is that we can’t be content to cure sick people and lecture them on how to stay well without also addressing these underlying social conditions that contribute to poor health and the glaring health disparities we see in our cities.

We cannot satisfy ourselves with doing one and not the other—particularly in light of the social unrest that has been happening here in Chicago and in my city, Baltimore, over the last year and a half following the deaths of Laquan McDonald and Freddie Gray. These and other events have provoked Americans to confront some difficult truths. Wherever your career takes you next, I ask that you try to channel those feelings into positive action.

After all, why put such herculean efforts into healing people and finding cures if we will stand for an environment that contributes to shortening their lives?

When we do make scientific advances, we have to ensure that everyone in our society—regardless of race or income—has equal access to the latest and greatest medicine has to offer.

In January, the director of our gynecologic oncology service at Johns Hopkins published an article looking at trends in the way we treat cancer of the uterus.

It used to be when you operated on a patient with early-stage uterine cancer, you did a hysterectomy by slicing open the abdomen. The incisions were large and sometimes could lead to infection, blood clots, major blood loss, etc. These days, minimally invasive surgery (laparoscopic or robotic) has become the standard of care, curing roughly two-thirds of these patients with far fewer complications than the old method.

At Johns Hopkins, we choose this method more than 90 percent of the time, unless there’s a complicating factor. Yet when our scientists looked at the national data, they found a troubling trend: African-American and Hispanic women are less likely to get the better, minimally invasive brand of surgery, as are patients who are on Medicaid or are uninsured.

- I wish I could say this was a shocking finding, but unfortunately, it’s all too common. Here are a few startling facts on health inequity in the U.S. today:

African-American adults are at least 50 percent more likely to die prematurely of heart disease or stroke than their white counterparts. - The prevalence of adult diabetes is higher among low-income adults and those without college degrees.

- The infant mortality rate for non-Hispanic blacks is more than double the rate for non-Hispanic whites.

- In Chicago, predominately white communities have much lower rates of overweight/obese children than communities that are predominantly African-American and Hispanic.

- In the area surrounding The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, the life expectancy changes dramatically from neighborhood to neighborhood— by as much as 20 years!

In 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” So what can we—or, more specifically, you—do about it?

Any strategy health care professionals develop to address population health must address the root causes of poor health, including poverty. Of course, the problems associated with poverty are incredibly complex, and breaking the poverty cycle requires an approach with many prongs, beginning with education.

I don’t expect you all to have the answers right out of medical school. All I ask, as you set off on your quest to eradicate disease, is that you take seriously your role as leaders in the community. The degree you are earning today confers a measure of responsibility, and I have total faith that your generation will get us closer to solutions to these pressing problems.

As busy as we are, trying to make our mark on the profession and, by extension, “human health,” we can’t lose sight of the people in the very neighborhoods our institutions exist to serve. I believe the medical community has a real opportunity to lead in helping to heal our cities, conquer inequality and create better opportunities for all. That work starts with the humanity and compassion in each of you.

Again, I want to congratulate you for this terrific accomplishment. We know you are going to achieve great things. Thank you.

Paul B. Rothman is the Frances Watt Baker, M.D., and Lenox D. Baker Jr., M.D., Dean of the Medical Faculty, vice president for medicine of The Johns Hopkins University, and CEO of Johns Hopkins Medicine. As dean/CEO, Rothman oversees both the School of Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Health System, which encompasses six hospitals, hundreds of community physicians and a self-funded health plan.

Paul B. Rothman, MD

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Commencement Address

The Medical Commencement Archive

Volume 3, 2016