It is a special time in medicine.

This is a time of the most rapid transformation in generations! You have scientific knowledge and technical abilities that far surpass those of your predecessors. You can multitask better than most. I know– I’ve seen you on the wards and in clinics—whipping out your smart phones, clicking on answers to clever questions barely out of my mouth. Us older physicians struggle to keep up with you.

What a privilege you have for a patient to say, “That’s my doctor!” You will care for thousands of patients during your careers. But remember, they will only see a small number of doctors. You will be very special to them in ways beyond your comprehension. They need an anchor, a belief that someone is thinking about and looking after them…and you will provide this without even knowing.

You will experience a better balance between your work and your family life than existed for our generation. You will no longer be such a slave to the profession in which family and friends who nourished us were too long neglected. Our multi-professional teams help us achieve this, with each member complementing and supporting each other. Such a balance is healthy, leads to better care and prevents burnout!

It is a challenging time in medicine.

The demographics are changing in our society. There is an increased demand for your services due to population growth and aging, as well as the arrival of healthcare reform. Soon, the majority of our nation’s population will be “ethnic minorities,” looking like New Mexico. Diversity brings a rich sharing of culture, language and values. But it also poses threats that could divide us. We must find

a way to overcome divides by race and ethnicity, by gender and sexual preference, by income and geographic isolation.

Your challenge is to bridge these divides, finding connections with patients far removed from your own upbringing, economic status, religious or ethnic beliefs. While we have the means to treat virtually everyone that crosses our doors, access to our care is not guaranteed—either because of transportation challenges, linguistic barriers, financial impediments or social marginalization of certain

groups.

Our nuclear families are shrinking as young people leave for schooling or for jobs. This leaves no grandmother around to offer guidance to a young, single mom about how to treat her feverish child in the middle of the night. In such an isolaisolation-

generating environment, clinics and emergency rooms often replace family for comfort, re-assurance and social connection. Some people feel so alienated, they have given up on the healthcare system except for late night runs to the emergency room for a neglected toothache, or an infected needle track, or for a sick teen who delayed treatment while waiting for access to the lone family car.

We will be challenged to gain skills and an understanding of domains far from our traditional areas of strength—population health, management of health teams, the business of medicine. Thus, our generation of physicians leaves you both with a legacy and a mess!

Medicine has a powerful history.

Look how rapidly our field has progressed in just a few generations and what a terrific time it is to enter the physician workforce.

First, let me recall some recent history: when your entered medical school four years ago. I’m sure the week you began medical school your grandma asked you, “What’s this bump on my arm?” You protested, “Grandma, I’m only a beginning medical student!” But she said, “Yes, I know, but just tell me what you think this is.” That’s when you found out that what you think of yourself in this

profession is not important—it’s what your family, your patients and your society thinks of you that is so very important.

There is an expectation of your competence and ability to heal which feels uncomfortable—an expectation you can’t fulfill. But, as time marches on, you’ll grow into these new clothes.

Now, let’s go back further in history and reflect on what doctors in New Mexico faced more than a century ago.

We begin with impotence in the face of diphtheria. In 1882, there were no immunizations against diphtheria, so the physician’s presence at the bedside WAS the medicine in his “doctor’s bag.”

Still, the cases were difficult:

Case 1- “I was called to bedside on Saturday. Found patient with difficult respiration and suppression of urine. On introduction of catheter, no urine was found in bladder. Performed tracheotomy; breathing very difficult; death in about 24 hours.”

Case 2 – “Patient a five year old…performed tracheostomy…lamp went out…operated with difficulty taking about ½ hour…spasms…died in about 12 hours.”

In Las Vegas, NM in 1914, doctors had many medicinal purposes for whiskey—to steady their own nerves, to use as anti-septic in the belief that they could kill off germs that cause diphtheria, even in kids, and as a pain killer. I relate to this last use, for I once had shingles, which felt like a hot branding iron on my side. I went to the local hospital and was prescribed narcotics, which didn’t

touch the pain. I was desperate. A colleague suggested I try alcohol. “I don’t drink,” I objected. But I bought a bottle of whiskey. It tasted terrible…and my pain disappeared. Swigging whiskey, I remained drunk for a week and felt no pain!

Prejudice and stigmatization were as rampant among our forebears as they are today with AIDS, mental illness, or in the attitudes of some toward immigrants. In 1904 a distinguished physician from Las Cruces warned of those with tuberculosis coming to NM for “the cure.” He said, “The army of tubercular invalids should be brought under control, promiscuous expectoration should be stopped

and every possible means taken to prevent these unfortunates from becoming a danger to the population… I most assuredly do believe that in return for the health-giving properties of our glorious climate, they should be willing to submit to some legal regulation!”

This sounds remarkably like our national political dialogue today.

You have skills and tools for diagnosis and treatment that many of us on stage could only have dreamed of when we were students. Not long ago, when I was a student, we treated congestive heart failure by bleeding patients and tying tourniquets to their limbs to prevent too much venous blood returning to overwhelm their failing hearts. Today, you’re equipped with powerful diuretics, medicines

to lessen heart stress, and coronary catheters to unblock clogged arteries.

Not long ago we warehoused the mentally ill, the developmentally disabled and the tuberculous in sanatoriums. Today, with stronger therapeutic means at your disposal, and better understanding of the pathophysiology of disease, most of these individuals live at home or in the community.

And not long ago, at the turn of the last century, most health providers were physicians. Today, physicians make up less than 10% of the health workforce—for we train with and rely on multi-professional teams to better care for our patients. While we train mostly in isolation from other health professions, we will spend our professional careers in interdependent collaboration with a growing number of health professionals skilled in vital areas which complement our own skills. We depend upon pharmacists, nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists and even community health workers.

And look what we face today. No matter what specialty you enter, the care you give will be affected by the social determinants of disease faced by your patients: educational attainment, income and poverty, access to nutritious food, yearning for social inclusion. These socioeconomic forces contribute more to health than all the medical care we provide. This is a humbling thought. But we’re

rising to the challenge. Community health workers, our frontline in addressing social determinants, are now hired for each of our primary care clinics. Our own Gwen Blueeyes sent me this note summarizing her work with one of our patients:

“Patient came to see me in clinic so I could help her obtain food. She appeared overwhelmed with her current situation. She said, “I’m losing my car at the end of this month because I’m behind on my car payments. I’m afraid I’ll be evicted because I’m unable to pay my rent. I receive some social security benefits, but it’s not enough to cover my living expenses. My local churches couldn’t find me any assistance.

I did the following: Helped her complete her food voucher benefits application, connected her with “adopted families” to

help pay last month’s rent, helped her complete paperwork for the Income Support Division to help cover cost of her Medicare premiums, and scheduled an appointment for her with the hospital Patient Financial Services Office,

which I’ll also attend to give her moral support.”

Now THAT’s an example of a powerful

addition to our heath team!

You should all be engaged in health policy. I want you to promise me that whatever field you enter, you will ALWAYS ask of the patient coming to clinic or admitted to the hospital bed, “How could this visit or admission have been prevented?” Our Chief of Neurosurgery asked, “Why do so many patients from rural hospitals with strokes and head injuries have to be flown to our Hospital at enormous

expense to patients and to those rural hospitals?” He set up a telemedicine program to review head CT scans sent from rural sites so he could advise local physicians on which patients to send, and which could safely stay put in their home community.

A pediatric endocrinologist wondered why her diabetic patients in New Mexico had to travel so far to Albuquerque for checkups. Half her diabetic children were on insulin pumps, allowing them to use the internet to download their glucose readings and send them to Albuquerque for review. This doctor can now advise patients on fine-tuning their management in their homes, sharply reducing

their trips to Albuquerque.

One of your classmates noticed that despite the recommendation that all patients with congestive heart failure contact their doctor at the first sign they are retaining too much fluid—3 lb in a day or 5 lb in a week- when asked, 4 of 5 patients admitted with congestive failure on our service had no bathroom scale. So she is working with cardiology and our hospital administration to propose buying $20 digital scales for all discharged patients with congestive failure who don’t have scales, which is aimed at reducing re-admissions for this condition.

And finally, a medical student and resident on our inpatient service explored how they could have prevented the admission of two patients admitted to our service in diabetic ketoacidosis. Both were poor, on UNM Care, and since insulin was so expensive, they had to use our hospital pharmacy to get affordable insulin. The problem, they discovered, was that our UNM Pharmacy was only open

8-5 when the patients were at work. They worked at jobs without benefits and feared if they took off from work, they could lose their jobs. The student and resident presented their findings to the UNM Pharmacy which agreed to stay open after-hours. Different generations teach each other.

Like Jedis, we taught you the ancient ways of diagnosis–using the “scratch test” to assess liver size, tapping muscles to check for “myo-edema” to diagnose protein malnutrition, and observing “sighing respiration,” a sign of anxiety.

But you upstarts taught our generation how to use dynamic documentation, how to quickly pull up x-rays on the computer, and how to access the latest evidence on your iPhones in seconds.

Older and younger generations in medicine offer continuity and mutual learning. I experienced this in my own home when I bought my first iPhone. I was typing away with my thumbs when my son looked over and asked what I was doing. “I’m texting,” I said. “No you’re not,” he said. “What am I doing?” I asked. “You’re e-mailing!” he said. “What’s the difference?” I asked. He had to show me that

little texting icon. Don’t ask me about Twitter!

Finally…why is your class so great?

I interviewed faculty and staff who worked with you over the past 4 years. And their general

consensus was: “You’re just so damned nice!” Your class character has made a great impression on all of us.

You have to be the kindest, most mutually supportive, most community-minded class in a generation. The welfare of your classmates and their academic and professional success, not just your own achievement, meant something to you. In the community, you helped the homeless, the immigrants, the disabled, the elderly and youth at risk. You’ve increased access to a life-saving drug- Narcan- for opiate overdoses; you’ve testified at the state legislature for health improvement bills; you’ve helped communities fight youth obesity; you’ve brought a range of services to inner city school kids, from dental health to sex ed; you’ve organized one of the largest, free flu shot clinics imaginable (>3,000 received shots in our parking lot).

You’ve shown the power of medical students as leaders, reviving and sharply increasing participation in the Student Council as a force

for positive change in our academic health center. You’ve organized mentors within your class to help all pass the Boards! And during Match Day, instead of rushing the table to grab and open your residency match envelopes like most classes, you politely approached the table calmly, helping each other find your respective named envelopes.

These are the skills that predict success in our highly social, interdependent field of Medicine. I was touched by an e-mail I received from one of your schoolmates relating an experience she had during her first year PIE rotation in rural New Mexico. She was attending a school-based clinic near her clinical site. Through fresh eyes, she summarized her following interaction with a teen patient:

“I can’t get out of my mind a 16 year old I saw today. She wouldn’t look me in the eye, and sat in the exam room sort of slumped over. I asked “What’s going on?” “My stomach hurts and I have a headache,” she said. Then all this craziness

started pouring out. “I haven’t slept in days,” she said. “My aunt keeps getting incredibly drunk. Last night my uncle was beating her and my aunt was so drunk, she wandered away.” “I can’t concentrate… My grandfather is dying. I

just lost 3 family members to alcohol. My mom says there’s not enough room in her house for me. I was just

separated from my sister…the one person who understands me. I can’t call her—her phone’s been disconnected.

I only eat what they have here in school—I get one or two meals a day…there’s no food at home. Even when I do eat, I sometimes throw up…I can’t help it…I’m so tired.”

With my mouth gaping, I collected myself. I got her some extra food from the school cafeteria, gave her a little something to settle her stomach, gave her a hug, and referred her to New Horizons. Deep down, I wanted to adopt her. She said she trusted me. God, she trusted me!”

THESE are the qualities that our field is looking for. Class of 2016, you’ve got it!

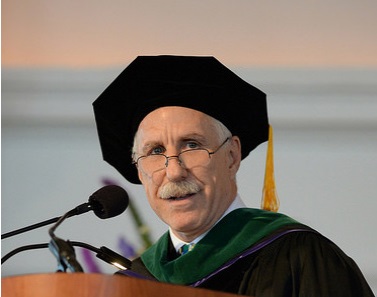

Dr. Kaufman received his medical degree from the State University of New York, Brooklyn in 1969 and

is Board Certified in Internal Medicine and Family Practice. He served in the U.S. Indian Health Service,

caring for Sioux Indians in South Dakota and Pueblo and Navajo Indians in New Mexico, before joining the

Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of New Mexico in 1974, where he has

remained throughout his career, providing leadership in teaching, research and clinical service. He was promoted

to full Professor in 1984 and Department Chair in 1993. In 2007, he was appointed as the first Vice

Chancellor for Community Health, and was promoted to Distinguished Professor in 2011.

Arthur Kaufman, MD

University of New Mexico

School of Medicine Commencement

The Medical Commencement Archive

Volume 3, 2016