‘Social injustice is killing people on a grand scale.’

– Marmot (2)

Despite the leaps and bounds that science has made over the past century, with all its shiny new techno-gadgets and ever-advancing drugs, the primary reason for our good health today lies in something much less sexy: vaccinations, clean water and sanitation- changes that we take for granted.

We live in a world that is changing every second. Bigger cars, faster phones, all the information at our beck and call: from the education that is offered to our kids, to the healthcare that is offered to our decaying bodies.

The hospital of today is a far cry from the one half a century ago. The minute you walk into a hospital your senses go haywire. You have stepped into the world of the future. The full scale of our technological advancement greets you within these four walls. The bizarre beeping overwhelms your ear canals, screaming into your brain as the alarms screech constantly in the background. The reams of wires trail along the floor of the wards, wrapping themselves around their patients like Christmas presents, offering nourishment to bodies overwhelmed with disease. We are living in the world of machines, and it is upon them that we place our hopes of immortality.

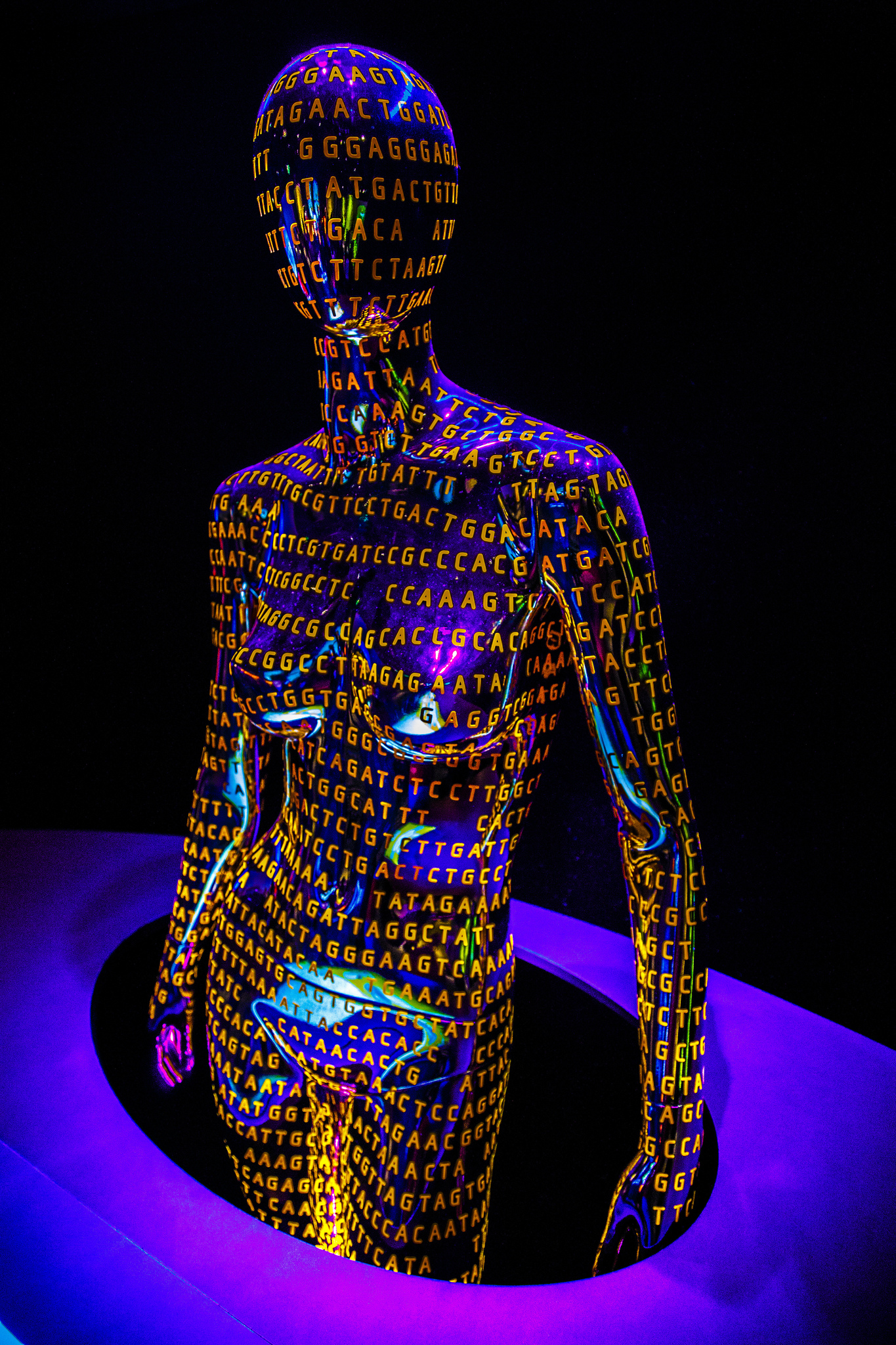

Everyone knows of the success story of Science. We are bombarded by the media, informing us of the next new cancer drug, the gene unlocked that will solve all our problems. What we forget is that we are not merely organisms residing within a vacuum. Nor are we machines ourselves, whose very pores can be zapped with electrodes, transforming our very identity. We are human beings living and breathing on this planet Earth. We digest the world around us. We are not merely scientists of the world within ourselves, of the DNA that twirls inside our cells. We are also manufacturers of the world around us; of the houses we live in, the food we eat and the lives we live. Perhaps the answer to a better, healthier life lies here instead.

But, is this the role of the doctor? Shouldn’t we leave this task to the politicians, to those who have the power to make these important decisions? Isn’t the duty of the doctor ultimately towards her patient, towards that individual who is sitting opposite, rather than to humanity as a whole? I believe Virchow, the German Doctor, described it best when he said:

‘Medicine is a social science and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale.’ (1)

Of course there are diseases that can only be fixed by looking inside our own bodies – diseases that come from within, that cannot be changed by any amount of control over one’s environment; Huntington’s Disease is one example.

But if you take a quick glance at the causes of mortality in both the USA and the UK, you will find that the majority of these diseases are significantly related to one’s lifestyle. The top leading cause of death in both the UK (3) and USA (4) is Heart Disease, which has very strong links with lifestyle, including smoking (5), a high-fat diet (6) and poor exercise (7).

In the past, when tuberculosis and polio wreaked havoc upon the population, the role of the doctor was to prescribe medication; to act as the priest who offered the gift of life through his knowledge and wisdom. Yet now, this power lies upon the patient. Our lives are no longer cut short by the plague, but by the pathways we choose to make while we are still alive.

The role of the doctor continues to change along with society. The doctor is the servant of the public. As our ailments in life continue to revolve around these pathways that we choose to take, so must the doctor focus her gaze away from the leaves of her prescription pad and begin to question the foundations of such paths; the reasons behind these choices, the thoughts and actions that lead a person towards their own destruction.

It is not enough to simply inform someone by saying ‘you need to do more exercise.’ Anyone who has made a New Year’s Resolution to do so will understand this. Even in the UK, a country where healthcare is free, one’s health is still dependent upon how much one earns. The richer you are, the longer you will live (8). How is it that in this day and age, this is still the case? Healthcare is a right. And as doctors, it is our duty to ensure this edict is followed. The politician may sit upon his throne and hand down his judgments, but it is the healthcare professional who is in contact day in and day out with the most vulnerable and marginalized.

Indeed, there are some excellent examples of attempts to try and balance this injustice within our society; free school meals in the UK which lead to improved nutrition in children (9) and the ban on public smoking to try and reduce passive smoking (10) are just two examples. These changes in legislation lead to the question: how much control should our government have over our own decisions towards our health? If someone wishes to smoke and drink all their life, then that is their right. Autonomy is one of the principles the doctor must follow; today’s healthcare system revolves around the patient and her choices. No longer does the doctor hold authority over the patient’s body. Yet this does not mean we cannot improve the world around us; we are still capable of building a healthier society, a society in which we will not only live longer, but be happier in as well. Free education and housing are two examples of societal changes that do not necessarily impose upon our personal rights, yet can lead to healthier childhoods and happier families.

Let’s say you are a single working mother – you are only just reaching your rent each month. You can only work part-time because you need to pick up your son from nursery every afternoon. You have no family who can look after him. This leaves little money for food, so you mainly feed your son. His diet is very poor, not only because of the little you can afford, but you yourself have never learned how to cook. Your own childhood consisted of fast food and the occasional apple or banana handed to you by a father who you rarely saw. You live in a very deprived neighbourhood. You cannot afford heating, and your son is constantly sniffling and coughing, hiding under his hole-infested jumper that you managed to grab from a local charity shop. You are isolated – your husband has left you, you have no one to talk to and your neighbours scare you. When you’re not working, you stay at home for your own safety, and ultimately for your son’s. You try to remain happy for your son. You want the best for him. But you are scared. You are scared for the future, you are scared about your next paycheck, you are scared about being burgled, being mugged, having your son taken away from you. You are scared about becoming a failure, of disappointing your son. You start drinking a glass of whiskey each evening to help you calm these anxieties. You gradually spend more and more money on alcohol, an attempt to grasp control of these spiraling criticisms that constantly call into question your ability to be a mother. But this does not always help. As the days turn to weeks, your thoughts begin to gain a voice of their own, almost screaming through your ears; you are a bad mother. A failure. Maybe you’d be better off somewhere else. Your son would have a better life without you. He wouldn’t have such an awful mother.

You eye the packet of paracetamol lying on the table. What would happen if you weren’t here? Wouldn’t your son lead a happier life? He would no longer have this dark mark tainting his existence. He might even be happy… What do you do?

In various points throughout this story, one could take out their pen and draw a mark where someone could have intervened. Not necessarily to offer medication or money, but things such as social support; someone to help look after the son in the afternoons, advice on how to apply for jobs, or housing in a more residential area. A helpful hand to hold on to during the darkest periods, a pat on the back, a shoulder to cry on, an ear to listen. How different would this story be if these simple interventions had been available?

It is very easy for us, the next generation, to caress our mobile phones and laptops that fit in both hands. It is easy to see the world as decaying pieces of rubble to improve, gadgets to insert, wires to wrap around and transform. No doubt this way of thinking has changed our healthcare; it has saved many lives. But we must never forget that humanity is not a machine itself. It cannot be controlled by our remote controls and our drugs; we must look further afield in order to truly appreciate the complexity of the human being. When we look at the human body, at a life that has been lived hard and is ending early, we see not genes that have played havoc, but decades of depression, underlying abuse, a cigarette to cope, a bottle of beer to forget. Addressing these problems is a task that requires us to go beyond our scientific skills. It requires us to understand the emotional lives of our patients.

“How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.”

– Anne Frank

References

- (with acknowledgements to Siân Anis), J. R. A. (2006). Virchow misquoted, part‐quoted, and the real McCoy. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(8), 671.

- World Health Organisation. 2008. Inequities are killing people on grand scale, reports WHO’s Commission [Online[. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2008/pr29/en/

- Office for National Statistics. 2013. What are the top causes of death by age and gender? [Online]. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/mortality-statistics–deaths-registered-in-england-and-wales–series-dr-/2012/sty-causes-of-death.html [Accessed: 13th October 2015]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Leading Causes of Death [Online]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm [Accessed: 13th October 2015]

- British Heart Foundation. Smoking [Online]. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/heart-health/risk-factors/smoking [Accessed: 13th October 2015]

- World Heart Federation. Diet [Online]. Available at: http://www.world-heart-federation.org/cardiovascular-health/cardiovascular-disease-risk-factors/diet/ [Accessed: 13th October 2015]

- Myers, J. 2003. Exercise and Cardiovascular Health. 107:e2-e5

- Royal College of Nursing. 2012. Health Inequalities and the Social Determinants of Health. London: Royal College of Nursing

- BBC News. 2013. All infants in England to get free school lunches [Online]. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-24132416 [Accessed: 13th October 2015]

- Bauld, L. 2011. The Impact of Smokefree Legislation in England: Evidence Review. England: Department of Health

Featured image:

Human Genome by Richard Ricciardi