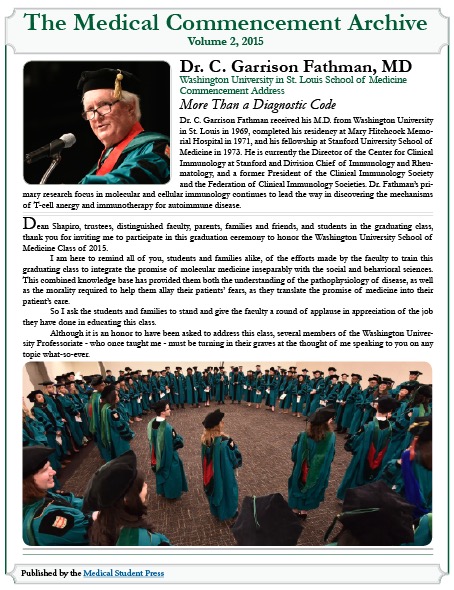

This week, Dr. C. Garrison Fathman’s 2015 commencement address at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis entitled, “More Than a Diagnostic Code” debuts via the Medical Commencement Archive.

This week, Dr. C. Garrison Fathman’s 2015 commencement address at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis entitled, “More Than a Diagnostic Code” debuts via the Medical Commencement Archive.

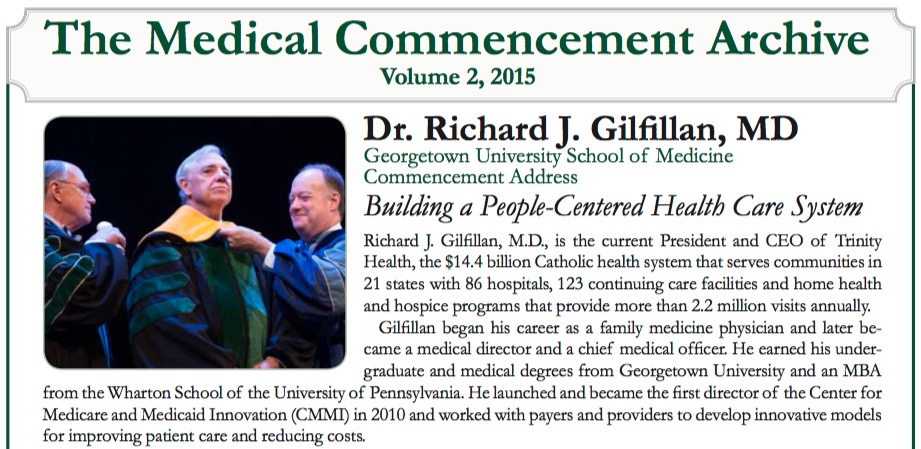

Dr. Fathman is a Professor of Medicine in Immunology and Rheumatology at Stanford University School of Medicine. Dr. Fathman received his M.D. from Washington University in St. Louis in 1969, completed his residency at Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital in 1971 and his fellowship at Stanford University School of Medicine in 1973.

He is currently the Director of the Center for Clinical Immunology at Stanford and Division Chief of Immunology and Rheumatology, and a former President of the Clinical Immunology Society and the Federation of Clinical Immunology Societies.

Dr. Fathman’s primary research focus in molecular and cellular immunology continues to lead the way in discovering the mechanisms of T-cell anergy and the pathophysiology and immunotherapy of preclinical animal models of autoimmune disease.

Dr. Fathman begins his speech by recollecting a somewhat nerve-wracking situation in his medical school rotation and reflecting on the importance of remaining humble in the face of knowledge:

“…you have an abundance of knowledge gained over the years of study already committed to this profession, but a dearth of practical experience. It is critical that as you enter into practice, you maintain a sense of humility in your knowledge as you interact with your patient.”

He continues by describing the dramatic changes in medicine as technology surges to the forefront of patient care, and encourages students to interact with patients physically and emotionally instead of simply recording information into a computer:

“…you must remember that the more skilled you become, the more specialized you become, and the more dependent on technology you become, the easier it becomes to lose your humanity by discarding your compassion and connectivity with your patient. You must continually strive to maintain your compassion and connectivity with your patient. This will allow you to maintain your humanity.”

He closes by reminding student to embrace the uncertainty of science and the opportunities it opens:

“Trust the education you received at this internationally esteemed medical school to help you make the right probability-based decisions, but don’t stop learning; continuing education is a life long requirement of the medical profession.”