My sophomore year of college, I had the incredible fortune of taking a course entitled “Literature and Medicine,” taught by a professor who inspired me in more ways than she ever will know. Professor Karen Thornber introduced me to the language of medicine and illness, and her course even now deeply affects the way I perceive the dialogue around, about, and in the clinic.

In particular, after reading Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor and Elaine Scarry’s The Body in Pain as part of the course (both of which I highly recommend—especially Scarry’s work), I was intrigued by the notion of the resistance of physical pain to language. Even when describing the pain of a paper cut, we resort to using metaphors and adjectives, comparing it to other sensations in an effort to fully encompass the experience. Is the paper cut actually “stinging” as a bee would? How would you differentiate describing the pain of a paper cut to a more severe pain? In fact, the adjectives we use to describe pain directly are quite limited. And unlike other sensations that can be carried from one person to another with words, pain is perhaps too heavy, too dense to be transformed into language. Rather, we use cries, moans, and tears to transmit the experience of pain.

Now, more than ever, I find Elaine Scarry’s perspective to be enlightening. For if she is correct in saying that pain is one of the few feelings too big to be molded into language, we can never truly express our pain to others through words. We can never fully describe pain or share it. Pain is therefore deeply isolating.

Three years ago, at the end of my Literature and Medicine course, I decided to delve into the relationship between language and pain by interviewing eleven individuals of different genders, ethnicities, and stages of life. I created a survey for them composed of a total of ten questions that included prompts such as: “Can you describe a physically painful experience?” and “Use one or two words to describe pain.” From these interviews, I produced a poem that attempted to convey the complexity of people’s reactions to and views of pain and illness.

Now, as I read this poem, I think about all the times I’ve asked patients to describe their pain, to rate it in severity from 1 to 10, to talk about its onset and relieving factors. How easy it was for me to write that information down and jump from one differential diagnosis to another without truly understanding their experience. And yet, even if I can’t truly know their pain, at least I can play a role in providing hope for healing and for relief. At least, I can listen and acknowledge the experience of their hurt. That is, to me, one of the greatest honors of being part of the medical profession.

Below is the product of my investigation of the “unsharability” of physical pain and an attempt to better understand how difficult it is to give it a voice (Scarry, The Body in Pain). What is your experience with listening to others try to express their pain in words? Have you found any insight into making it easier for others to talk about their pain? Or do you find that your experiences differ from mine? Feel free to comment or email me at stephanie.wang@jhmi.edu. I would love to hear more!

*Note: Italics indicate quotes taken directly from interviewees. The majority of the content of this poem is based upon the interviews.

Here and There

We alternate between here

and there. You see,

there is a line, crooked and cracked,

an emaciated demarcation,

a highlight in air, breathlessly coughing

and smelling of phlegm.

It would be very painful

to cross it, this line.

Unable to be broken,

we wax in and out.

How to describe such a thing?

Mind-numbing and distracting,

distasteful, unpleasant, depressing and miserable.

Regret, helplessness, extreme

sadness. Sick,

like you’re sick.

What pulls us along is an anti-happiness,

it drags us past the line,

it is an anger and an envy, a struggle for

God knows how long.

It nests in suicidal thoughts,

family problems, rolled-up eyes, severe

shock, pain.

Pain, it’s like,

it’s a…

A scar, a feeling I couldn’t recognize,

a breaking of the arm, a finger cut off,

a scrape of the knee,

a ball to the head, hurt jaw, appendicitis, unbearable

distress, tears, a scream, almost

dying. Well,

I don’t like pain.

You can’t think, can’t do anything. Panic,

confusion. There is a leaving behind,

a change of identity—

you lend a hand

because you have to. You are supposed to do that.

To help. The pity, the obligatory sad eyes.

I wanted to stay away, I was really

annoyed at the hack of her cough,

her eyes, feverish.

I actually wanted to avoid her, avoid

crossing the line.

The millionth tripping from one side

to another sounds like fish scales,

feels like rain, the starting

and stopping, the forgetting and remembering

of hoarse throat, runny nose,

seasonal allergies, itchy and flushed.

Forget about it,

concentrate on something else, calm down,

try to ignore it for

telling people won’t change anything,

screaming and shouting won’t do anything,

It’s like no one understands, I deal with it

myself, I can kinda block it out.

Everyone does things to alleviate it.

I’ll pray, but the only thing

that really makes it go away is time.

Halos of stars plaster the sky

and the constellations only appear

when a story is made for them. Let us figure then

a way to line everything up against this thin mark

between two vast caverns. The body flung

from here to there

is yours and mine. As it will always be

your body, our pain.

Our pain, my body.

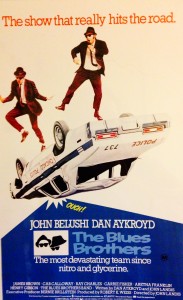

Featured image:

Pain by trying2

Occasionally between lectures, some instructors will play music through the lecture hall sound system. As I sat waiting for the next lecture to begin, the Blues Brothers’ version of “

Occasionally between lectures, some instructors will play music through the lecture hall sound system. As I sat waiting for the next lecture to begin, the Blues Brothers’ version of “